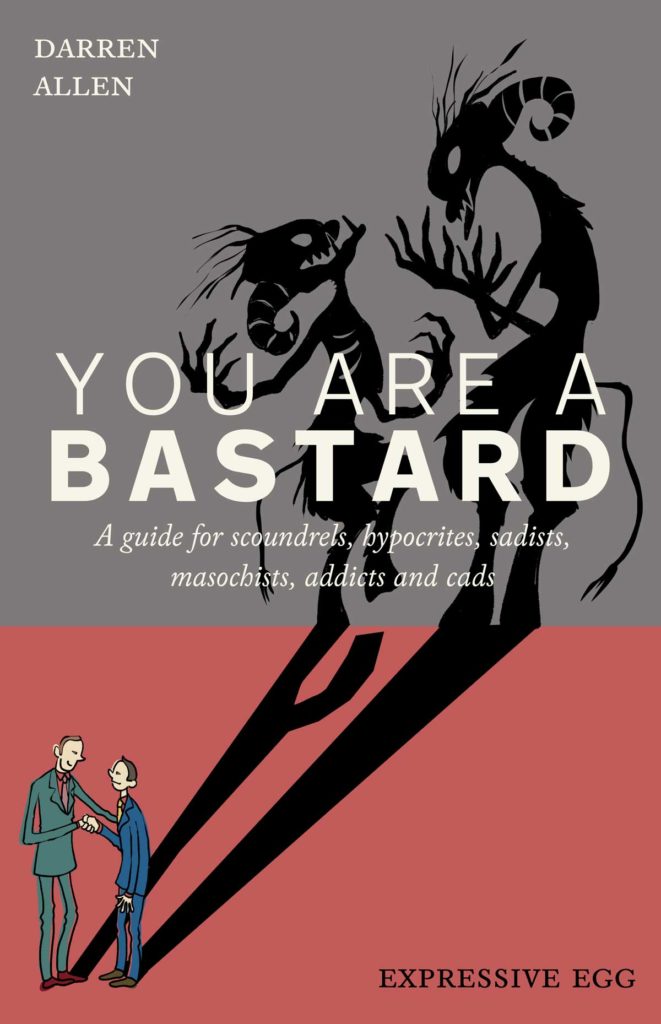

You Are a Bastard

1. Conscience: Private Enemy Number One

You – and by you, I am largely addressing men1 — may perhaps have noticed that you are self-interested, vain and essentially violent. In short, a bastard.

People are apt to consider their bastard-nature, or lack thereof, as the shallow linguist considers his competence. ‘I am good at the language,’ he thinks; after going on holiday and only talking of prices. Because we cannot perceive the whole of ourselves, because the extent of the self, like that of the vocabulary, appears only in circumstance, we ludicrously assume that ‘I’m fine’ or ‘I’m happy’ or ‘I’m good’2 The truth is quite other, but the circumstance is lacking to show it. Your world is designed, from the ground up, to prevent such unpleasant circumstances arising. Some self-revealing situations do poke their irksome truths into your awareness, and quite regularly, but they are dealt with swiftly and efficiently, long before your cruelty, or cowardliness, or greed can be seen and known as they are.

Right now, for example, you might feel quite well-disposed towards your fellows, no significant guilt troubling you, no anxiety, thwarted ambition or expectation ready to lash out; but then life will throw up a challenge — an unexpected temptation to gorge yourself, a cruel word or tone from someone at work, a reminder that your house is built on sand — and you baulk, flake or welch, you lose your temper, panic, or behave quite disgracefully. These ignoble deeds always produce unpleasant sensations. These we call conscience; the feeling of the self revealing itself.

Exposure! Code Red!

Because sensations of conscience — shame, guilt, duty and so on — are feelings (or, to put it a little more specifically, emotions), which is to say prior to both thought and to justifying language, you can then describe them any way you like. A twinge in the chest — you could call that guilt, fear, boredom, or indigestion. So of course3 you choose something favourable to yourself. We call this a justification. Then, with your actions, you build more ideas, evidence and incrimination-suppressing actions on your self-justifying description in order to suppress or validate it.

Let’s look at an example. Let’s say 1. deed you have been neglecting someone, a child perhaps, a girlfriend, an old mum who’d love to hear from you, and 2. conscience a sensation of discomfort is building up inside. Not nice, that feeling — but the unpleasentness can’t be coming from you, can it? It can’t be your fault. It must be… hmm, let’s look at the options. It must be 3. justification that you’re bored, in need of some fun. If you 4. suppression-validation go out and get drunk, or have sex maybe, or get lost in an exciting video game, you’ll forget about the guilt, which will prove to you that the problem wasn’t guilt after all, but a completely normal human need to have some fun.

Another example. 1. You are madly obsessed with cleanliness. 2. Someone shakes your hand and you immediately take out a wet-wipe to clean yourself. This makes you feel bad (awkward, ridiculous, etc.). 3. But that bad feeling must be because they are dirty, inconsiderate, perhaps even nasty. 4. You get angry at them, purging yourself of the discomfort and, most likely, they’ll react badly, proving to you that they are not a good person.

One more example. 1. You wish to annihilate a country in order to gain access to its oil reserves. 2. Some troublesome pinko discovers that you’ve got shares in a construction company which stands to benefit from the invasion. 3. Feels awful that; must be because your critics are unpatriotic terrorists hell-bent on undoing civilisation. 4. Lock them up or get them fired; gets rid of the problem and makes you feel a satisfying rush of victory at having overcome an enemy.

Okay, okay, one more, a subtler one. 1. You are annoyed by something your partner does; perhaps he doesn’t give you the right kind of attention, or maybe she is unresponsive when you make love. 2. You feel agitated all day, it comes between you both, maybe making sex difficult, or causing you to lash out weirdly over trivial matters. 3. As you’re a bit of a patsy, perhaps into eastern philosophies, you decide well it must be your fault, you’re not sufficiently accepting, enlightened. 4. You feel your emotion, containing it, or you meditate, or go and see a guru, or do some yoga — anything to feel okay with the pain without having to actually do something about it, address the problem, tell your lover they are treating you casually or walk away from this stupid relationship that you are, actually, addicted to.

I could go on listing examples forever. The natural response to doing wrong, to being addicted (to talking, to the internet, to narcotics, to attention, to power, to money, etc.), to neglecting your duty4 (to your children, to your parents, to your body, etc.), to losing your presence (allowing your restless thinking-wanting-not-wanting ego to trample over the present-moment), to obsessions (excessive purity, excessive control, excessive thinking and planning, etc.) and to cowardliness (avoiding necessary confrontations, afraid to let go of the known, backing down from exposure, etc.) is a bad feeling in the body. This is conscience, something which men and women will go to absolutely extraordinary, outrageous, insane (sometimes hilarious) lengths to ignore justify and suppress. It’s no exaggeration to say that conscience is private enemy number one.

2. Your Bastard Heart

These shennanigans are possible because your bastard self is essentially pre-reflective. It’s not a conceptual entity, living in your abstract mind, but an unconscious being (actually, as we shall see, unbeing) which you feel as emotion, if you feel it at all. It seems so easy to ignore. Focused, as most people are — particularly most men — on a screen of thoughts which I take to be I, along with a conceptualized external world, the primary inner reality of the bastard self is hardly intuited, and when it is immediately rationalised away by focusing on the secondary head-self.

This is why it is so infuriating, and pointless, arguing with people; because you’re not arguing with their mind, which will twist and turn (in an entirely predictable manner) to allow the self to remain untouched. You’re really arguing with their inner bastard, but this is not accessible to the awareness of the person you are talking with. The only way you can ever really verbally influence someone’s basic bastardy is to calmly point it out in the moment it appears. ‘See, you’re not really listening to me. Right now, your mind is elsewhere…’ But even that’s unlikely to have very much effect. The roots of the bastard run very, very deep.

This is why it is so infuriating, and pointless, arguing with people; because you’re not arguing with their mind, which will twist and turn (in an entirely predictable manner) to allow the self to remain untouched. You’re really arguing with their inner bastard, but this is not accessible to the awareness of the person you are talking with. The only way you can ever really verbally influence someone’s basic bastardy is to calmly point it out in the moment it appears. ‘See, you’re not really listening to me. Right now, your mind is elsewhere…’ But even that’s unlikely to have very much effect. The roots of the bastard run very, very deep.

The only thing that the basic bastard self learns from, really, is life — rejecting, refusing, smashing, pounding, destroying life. When life smacks the bastard self down, when the addictions that it feeds from are denied, when the means by which it conceals itself are unavailable, when, in a word, it is heartbroken (bastardbroken) then the bastard can see something other than itself. And that’s why this is such a heartbreaking world. You have to lose your money, you have to have your good name trodden on, you have to be frustrated, you have to lose your loved ones, be betrayed, have your buttons pushed and your tidy-green overwhelmed by commoners. Your bastard heart must, and will, be broken.

3. Beyond Bastardy

It’s funny what the justifying mind will admit. People will happily admit to doubt, poor memory, low self-esteem, failing eyesight, clumsiness, anxieties, phobias or any other ‘mental illness,’ but never to being mean-spirited, narrow-minded, loveless, cruel, unconscious or lacking humour. Does this apply to you? Have you ever said, ‘sorry I’m basically mean-spirited’ or ‘I’m afraid I don’t have a very good sense of humour?’

Generosity, open-mindedness, humour and love are the basic non-intellectual realities of an open-heart, of the essential non-bastard I. The bastard-self in you, however, cannot perceive them. It has no idea of how much deeper your love can go, or how much funnier you can find reality, or how much more essentially generous or conscious you can be. Again, just as the limited linguist has nothing in its immediate experience (the words it is attending to now) to judge how much more language there is to learn, so the bastard-mind has nothing in its experience to judge ‘deeper’, and so its own limits must be the limits.

Now you might be thinking here; well this must apply to everyone all the time, surely? It’s a logical impossibility for experience to experience beyond itself, and so nobody can ever know what a bastard they are. But t’ain’t so. I can experience something beyond the me that I ordinarily think and feel myself to be. In these rare — all too rare — miracle moments that which seems to be experiencing my life, the self, dissolves into something more fundamental, a non-bastard state ‘beyond itself’. Although the self cannot grasp this — and therefore remember or literally describe it — I, the conscious reality behind my self, can keep itself plugged in, as it were, with its toes in the sea of mystery, while aware of the limits of self. From here I can see myself being cowardly, tight, cruel and humourless — and in the seeing, be free of it.

A common example of this, as I’ve said before, is when I realise I am talking too much. In that moment ‘I’ — the conscious self — sees ‘the self’ — the unconscious selfish gabbler. Popular psychology and philosophy would have it that there are two (or more) I’s in here, but there’s not. There’s all kinds of selves, for sure, but there is only one I which is conscious of them and which, in that consciousness, can shut them all up.

The authenticity of consciousness, its stamp of truth, is in the universal appreciation that its appearance evokes in others. When someone is afraid, vain, caught up in a blind self-mare and stops, raises themselves beyond it, perhaps with a chuckle, and says ‘sorry, I’m being a bastard!’ — or even just ‘Jesus I’m boring myself’, oh the relief, the delight!

It’s not, therefore, your bastardy that is the problem, it’s that your bastardness is all there is in there.

4. A Bastard Like Me

I am a bastard too. I am less of a bastard than I was, so this section is in the past tense, but I have been, in my life, a total bastard! I’ve stamped on the hearts of those who loved me, I’ve gracelessly climbed over one women to get to another, I’ve shrunk, pathetically, from my responsibilities, I’ve been brutally unaware of the mood of the room, I‘ve been jealous of the brilliance of others, even my dear friends, I’ve been embarrassingly over-excited, I’ve got off on my specialness or my ‘sad sad story’, I’ve stolen — and not from corporations, from people I love (admittedly that particularly vile act was when I was about twelve, but anyway), I’ve lied in order to make myself seem more important or to avoid exposing my guilt, I’ve been afraid to tell people that I love them, I’ve had extraordinarily sordid sex, I’ve said some staggeringly cruel things to people, I’ve been completely absorbed in myself missing all manner of cue and I’ve lost my temper so disgracefully, so shamefully, I can no longer fully remember the events in question, having erased them. And I am an ordinary person, quite a nice one, you’d probably find.

There are some species of bastardy that I am not given to of course and to wash the taste of the above paragraph out of my mind, and hopefully yours, I must say that I don‘t hold grudges or resentments for longer than about two seconds, I’m not mean or tight, I’m not ‘the jealous type’, I’m not a blabbermouth, I don’t do self-pity and, although part of me is certainly quivers with fear before confrontation and uncertainty, I’m not a coward and I don’t compromise for an easy life or trade my finer instincts for convenience or for money. Like everyone, you see, my bastard-nature is, if not unique (only ‘I’ am really original) then at least particular, which is one of the means by which it seeks to defend itself. The bastard self has an irresistible attraction to the faults of others which it is not constitutionally prone to. I am, for example, far more forgiving of anger and cruelty than I am of cowardliness and grudge-holding, which particularly disgust me. And you’re the same, aren’t you? You’re much more willing to let bastards like you off the hook while those who are selfish in ways you don’t tend to be, get a right bloody kicking!

As do, of course, those whom ‘but for the grace of God’ commit psychological crimes that your situation has put beyond temptation. This is a particular failing of the the rich bastard, very happy to moralise about theft, for example, or direct forms of violence, or even racism and sexism; bastardies that the poor are, for obvious reasons, more prone to. Take away their money, their social standing, their professional security and the indirect support of the system, then see how wonderfully moral these nice ‘rich’ people are.

The old bastard is also prone to hurling judgements at those with energy to sin in ways he has long forgotten. ‘You were young once!’ a kindly wife might say, but the old bastard sees nothing but inconceivable ignorance.

5. Ways you are bastard

You justify your selfish moods. Anger, depression, anxiety, coldness, over-excitement: ‘It’s your fault,’ you say, ‘or God’s fault,’ or ‘my parent’s fault,’ or ‘the fault of my ‘mental illness’. First rate, top shelf bastardy. You are quite the genius for excuses. You blame everyone and everything but your self but your cleverest trick of all is to blame your self; nothing quite gets you off the hook like agreeing.

You get wrapped up in yourself during a conversation, eyes inward, enjoying the sound of your own voice, attention narrow — or just on the alert for a reason for you to continue talking.

Through fear of stillness — a felt fear of being without stimulation which goes by the name of ‘boredom’ — you indulge your self, working it into a selfish ‘up’ (indulging in contention, violence, coloured lights, buying things, gossipping, complaining and other forms of masturbation) which, a few hours or days later, descends into a selfish down.

You go over past hurts in your mind, over and over and over, imagined futures of success, imagined relationships of sexual abandon, imagined routes out of imagined problems, working away at yourself, day and night, night and day, hardly aware of anything or anyone.

You — particularly you men — are obsessed with sex, utterly totally insane with fuck-wanting. You’ll do anything for release, no matter how sordid, no matter how much someone gets hurt. The more sensitive and romantic among you will dress this up in higher desires, aesthetic ones, or spiritual ones, but not far under is the old beast which, after it gets its way, after all the pain of loveless fucking, you do it again. And again. And again!

And you men, you have to win! You cannot stop until you’ve won; but of course, with most things (such as arguments) you never can win, and with competitions, how long does the victory feeling last? A day, a week? Not that there’s anything wrong with striving for victory, but this manic, relentless having to win? Utter bastardy!

You tell people what to do; people who aren’t interested, who don’t want your advice, who can’t listen or even perhaps understand. You live your life through your children, you order your employees around, you get off on power…

…or you’re a doormat, getting off on being told what to do, falling at the feet of someone who orders you around, relieves you of the burden of freedom, validates your comfortable sense of worthlessness. Being mindful and meditating is, for some bastards, part of this — always better to feel your emotions, be present and godly, than actually do something about the problem.

You say everything you’ve ever done has been for your family, that you want them to have a better life than you, that you want them to be safe… and you do! But, all the while the bastard is getting off on being the hero, the martyr, the saviour.

You accept the system, basically. You complain of course, about various aspects of it, but you’re quite comfortable being domesticated, confined and coerced, and domesticating, confining and coercing others. Or lying to them. Perhaps you’re a professional, very subtly feeding off your system-granted privileges, or maybe you’re very rich, with the money-power the system grants you. In either case: bastard.

Innocence annoys you, genius offends you, nature bores you, freedom terrifies you, love confuses you, death horrifies you, consciousness mystifies you, the present moment passes you by.

You don’t really see anyone or anything. Everything is filtered through the self, and so only ever experienced relatively; how the thing or person relates to you (like, don’t like, love! mmm, not so good, booorrrring!) or how they relate to each other (their various classifications, prices, weights and measures, etc, etc, etc.). What the thing or person really is, its real nature, completely eludes you.

6. The origins of bastardy

Bastards begat bastards. Parents, and beyond them, societies, which coerce, repress, torture, deprive or ignore their children, create more bastards; or rather, the inner bastard is always there somewhere, and the bastard-like conditions within the home, or the school, or the place of work, feed it, elevate it over conscious experience, and possess awareness, like a bastard demon which gets handed down generation after generation. And so bastardy has been steadily getting worse since the first bastards appeared around ten-thousand years ago and began spreading. Violence towards children, hostility towards women, unconsciousness and insensitivity, brutal repression of ordinary people and outsiders, warfare, sickness, and general human misery have spread with them, creating more bastards which create more misery, until their bastard world covered the earth, a process which is now well-documented in the anthropological record and not a matter of much contention.

Before the first bastards, and outside of the metastasising spread of this bastard civilisation, non-bastards were common, indeed the rule. In the distant past, there were no bastards at all. Certainly there were times of privation, there were bursts of anger, there was childlike huffing and puffing and the glimmerings of ego, but the full-blown bastard was nowhere to be found. So what happened?

Let’s start by reminding ourselves what ‘bastard’ means. We used to say it was someone born out of wedlock. This only became a stigma when the institutional church got their hands on marriage and made such births ‘illegitimate’ or ‘low’. Today, and here, the word means despicable, insensitive, selfish. Not ‘born out of wedlock’, but ‘born without love’. A bastard has not really ever been loved and is unfamiliar with the unconditional reality of true love. Unconditional means that it requires no condition to exist. Relatively, in the measurable world, I love you because you are my wife, because you are my daughter, because you make me laugh, because you’ve done well, etc. Absolutely, or ultimately, however, I love you for no reason at all. I just love and you are just lovable. This shared experience—subtler really than anything we normally call a ‘feeling’, but extraordinarily potent and vivid—releases one’s grip on the relative things and conditions and ideas and objects of the ordinary self, the conditions that I think I need to be okay, and provides access to an absolute state of unconditional okayness.

This is our original state, that children and primal people live in. But around ten thousand years something intervened. Somehow the conditions became more important than the unconditional. Men and women started to need things to be content; security, pleasure, excitement, power. Unconditional okayness began to recede until it became ‘abstract’ and the non-bastard life we lived together became mythic, a story, unreal.

Somehow the bastard self had grown to such a size that it was able to take over and monopolise experience. I — the conciousness behind self — became a slave to self, unable to stop thinking, wanting, worrying and needing; afraid of all the states which threaten the conditions that self believes it needs to be happy. With the bastard self in charge I could no longer be really spontaneous, or really original. I felt constrained, but unable to quite put my finger on what it was that was hemming me in — because it was ‘me’.

7. Beyond the Bastard

Bastards have only a limited grasp on the present moment. Most of the time they spend thinking about the past or future, or grabbing on to isolated bits of the present, things they want or they don’t want or that relate to them (‘ooh, I like that, that’s not so bad, hmm, that reminds me of…’ on and on it goes, this inner isolated-object based jib-jab). This they do, because they are searching for something to fill the hole where the absolute should be; or rather already and forever is, but unperceived. They learnt to do this when they very young, and when mankind was very young; so long ago they have forgotten what life was like before they slipped into their bastard selves.

Sometimes, in an instant, the bastard is gone. An unnameable sense of something else rises in consciousness — something mysterious, and yet intimately me. You feel good, fresh, present, generous, uninhibited… but not for long. You soon slip back into bastardy.

The bastard is strong. He won’t be defeated by luck. A nice day out, love-affair, a satisfying game of football, a moment’s grace — they’ll shut him up for a bit, but they won’t put him in his place. He’ll sit back and wait, biding his time, then return to his throne just as soon as you’ve got home, or got back to work, or the honeymoon ends. He knows you can be strong and conscious under certain favourable conditions, so he just waits until you are weak again.

To defeat the bastard you must take the battle to him. You have to root him out in his lair; your own weaknesses, your own compromises, your own fears and addictions, always hidden behind your own justifying strengths. It is only by being honest in your depths, practicing presence when your back is against the wall, facing up to what you most fear and turning your back to what you most crave — and doing this all the time5— that you can put the bastard in its place, chain the fucker up, and have him work for you.

Because you see, you can’t kill the bastard. He is, in a sense, immortal. But you can domesticate him, and then he’s a marvellous servant, very effective. But of course you can only do this if you’ve had enough of being domesticated by him.

Have you?

Notes

- Women can be bastards too, but their bastardliness tends towards a different flavour of horror, bitchiness, which also has somewhat different causes. Not entirely though; the bitch overlaps with the bastard, so this account is of use to women too.

- ‘That failing is evil — not mine’.

- If you can perceive them at all — many cannot. But that’s another matter.

- Not a very fashionable word that, these days; duty.

- The conscious man is not identified by the intensity of his consciousness, but by the constancy of it.