I visited St. William’s house last year…

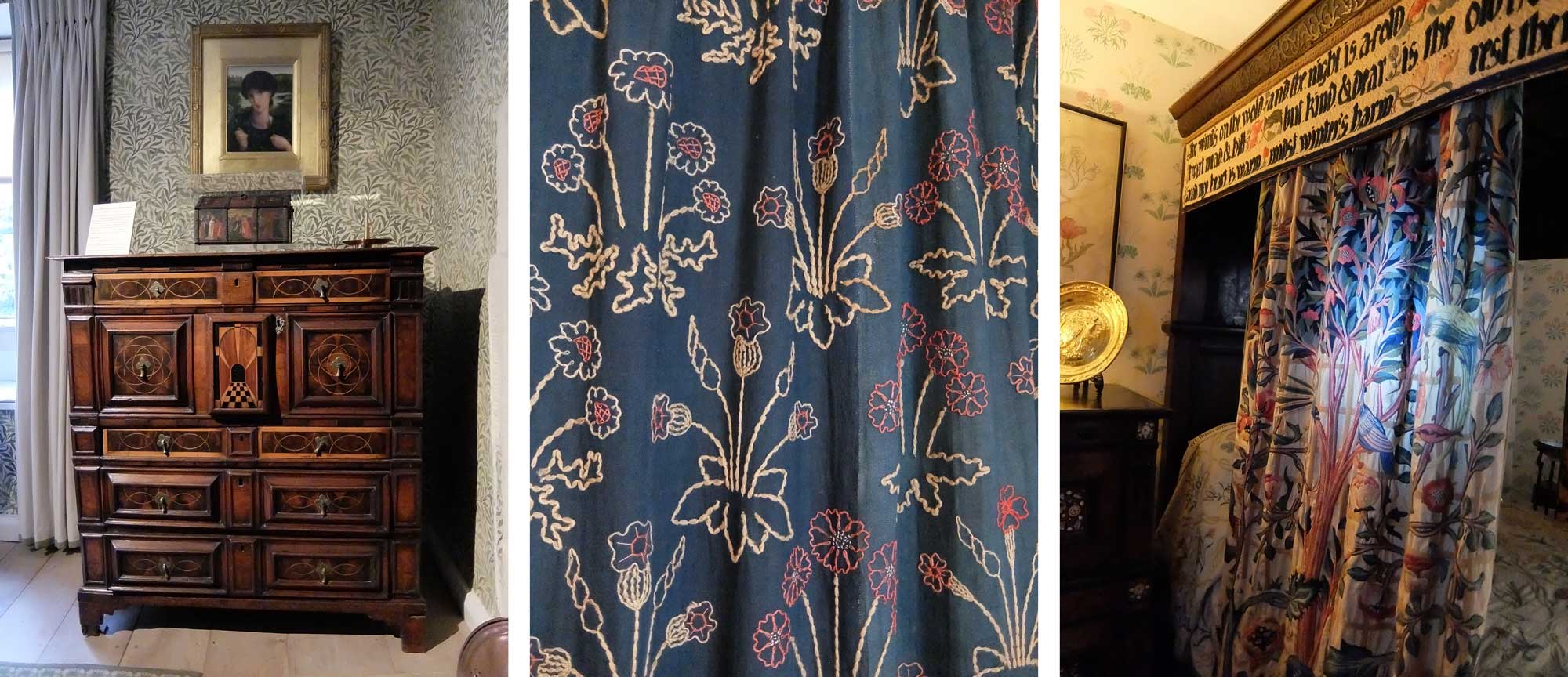

As extraordinarily beautiful as you’d suppose, if you’re a Morris fan. Profound simplicity, heart-warmth, delight-inducing attention to detail, spaciousness and exquisite good taste.

As ever though, in all matters Morris, but a swift, sidelong glance at his convictions. Nervous cough, ‘Morris was a socialist’, leave it at that, move on into the next gorgeous room. Ahhh.

Apart from being the greatest English craftsman of the last two hundred years (reintroducing, single-handedly, the miracles of medieval textile-design, dyeing, weaving, embroidery, stained-glass and so forth back into our artistic tradition) Morris also had what I’d call spiritual dignity. Even his enemies conceded that he was incorruptible, while his friends knew him as ‘one of nature’s true aristocrats’. Blustering, foolish, impulsive, short-tempered to the point of childish, but of shining integrity, which led him to socialism.

Not to the intellectual socialism of Marx, nor to the cowardly reformism of Dickens and Ruskin (who always stopped short of the final truth — class) and certainly not to the horrors of Fabianism, which disgusted Morris.

Morris’s socialism was simple, direct, practical and got to the root of the problem — at least as far as society is concerned. He never ventured beyond straightforward good sense, wherein lay the limitations of his mind (and also of his rather dull poetry), but also his power, greatness and human warmth. As with Wilde there is a strong argument that the best of his work, state-less and free to a fabulous extent — and opposed to ‘mainstream’ socialism and reformism — was, like that of his friend, Peter Kropotkin, anarchist.

MORRIS SAID…

‘The most grinding poverty is a trifling evil compared with the inequality of classes.’

‘…he heard Morris talking and walking about in an excited way, and went to inquire if anything was wrong. “He turned on me like a wild animal—‘It is only that I spend my life in ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich’”’

(from EP Thomson’s biography)

‘Luxury cannot exist without slavery of some kind or other, and its abolition will be blessed… by the freeing both of the slaves and of their masters.’

‘…the man of the most refined occupation, student, artist, physician… shall be able to speak to him who does the roughest labour in a tongue that they both know, and to find no intricacy of his mind misunderstood.’

‘What we should press upon reformers, is that they should set a higher ideal before them than turning the life of the workers into that of a well-conducted reformatory or benevolent prison; and that they should understand that when things are done not for the workers but by them, an ideal will present itself with great distinctness to the workers themselves… ’

‘We have said, “Buy this or—take a bayonet in your belly!” People don’t want the goods we offer them, but they are poor and have to buy something which serve their turn anyhow, so they accept… Their own goods, made slowly and at a greater cost, are driven out of the market, and the metamorphosis begins which ends in turning fairly happy barbarians into very miserable half-civilized people surrounded by a fringe of exploiters and middle-men varied in nation but of one religion—“Take care of Number One.”’

‘The factory would be a centre of intellectual activity, and, besides turning out goods useful to the community, will provide for its own workers work light in duration, and not oppressive in kind, education in childhood and youth, serious occupation, amusing relaxation… leisure… beauty of surroundings, and the power of producing beauty which are sure to be claimed by those who have leisure, education and serious occupation.’

‘I have never under-rated the power of the middle classes, whom, in spite of their individual good nature and banality, I look upon as a most terrible and implacable force.’

And finally, for anyone out there fighting work, some words from the patron saint of wage-slavery refusers (click image to download the classic essay);