THE OLD MAN IN THE SQUARE

In the Wordsworth poem ‘Resolution and Independence’ the poet, wandering over the moors, comes across a old guy gathering leeches in a pond who gives the poet some advice on facing the future with stoic resolution. The understory of the poem, and of the lesson of the old man, is how integrated he is with his environment, with the rocks and moss and light and water…

Upon the margin of that moorish flood

Motionless as a cloud the old Man stood,

That heareth not the loud winds when they call,

And moveth all together, if it move at all.

Not long after reading this poem I went for a walk through the town I live in (a kind of vast old-people’s home in remote western Spain). It was an extraordinarily mild and quiet afternoon, the friendly sun strolling across the sky as lazily as the old men in the town square, one of whom seemed to me, like Wordsworth’s leech-gatherer, fused to the world, or as if grown up from it with the almond and myrtle trees.

He was sitting on the low wall that surrounds the small tree-lined square, leaning sideways against an orange tree, one hand on his knee the other lightly resting on a cane, wearing a tweed-cloth flat cap, tank-top and dark green beaten-up jacket, similar to the other old fellas around town, but he wasn’t as stocky as them, as heavy-set or as bullish, but delicate, cat-like and gentle. As we passed he looked up at me, without moving and smiled shyly as if to say ‘yep, you’re right, I too was built eight hundred years ago’.

But then you could say the same of Vancouver-dwellers, Tokyo-dwellers and London-dwellers. They are also part of their world. Modern cities are places of pigeon shit, burger-boxes, plasma-screens, choking trees, corporate coffee bars and smooth design studios… and the people who live in cities generally look like they are part of that too.

And yet, if my old fella walked through central Madrid he wouldn’t look as out of place as his grandchildren do when they turn up here for their holidays. In Madrid nothing is out of place, because the aesthetic is ‘out-of-placeness’.

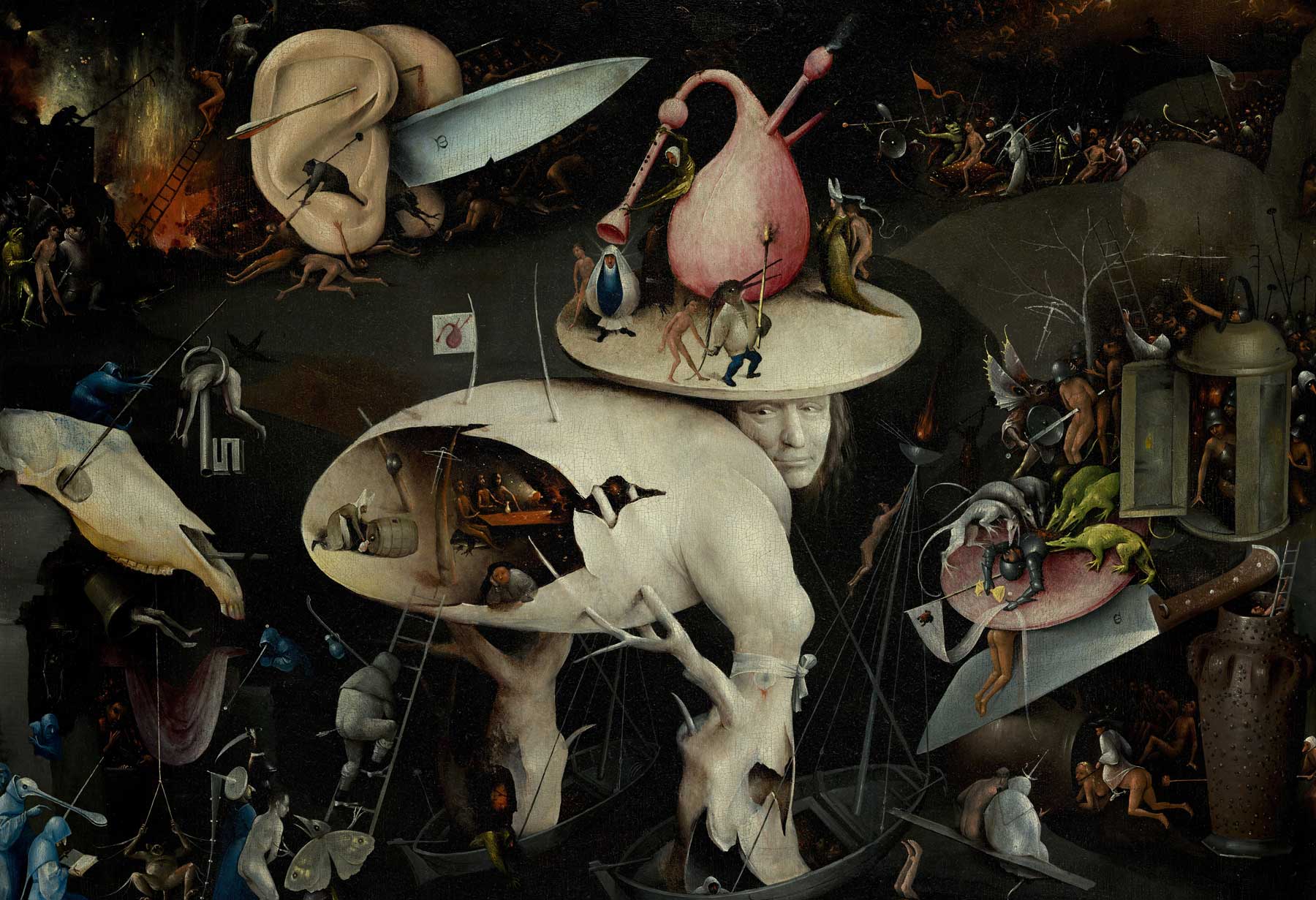

BISH BASH BOSCH

In the Madrid Prado you can find Hieronymus Bosch’s almighty (and surprisingly huge) triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, which represents heaven, earth and hell (detail shown below). The essence of Bosch’s hell, the nightmare of it, is that nothing is related to anything else — everything is intensely itself, fragments, unrelated to the whole except in their meaninglessness.

Bosch’s hell, painted half a millennia ago, seems to prefigure the schizoid modernism of Chirico, Dali and Tanguy, in which nothing really relates to anything else; the arbitrary rules. The difference being that while the modernists (and postmodernists) thought they were creating art, Bosche knew he was depicting hell. He knew that fragmented isolated objects hanging in a contextless void was the world of the damned, the enemy of life. And — I suspect — he knew we were heading there.

Modern and postmodern artists, in contrast, believe they are being ‘original’ in smashing the world into fragments — it is so passé to have a man with one nose (or a head with anything but a nose), a woman with pink skin, a table you can actually use, a house with a roof over walls… Likewise, modern producers and editors believe they are being ‘diverse’, ‘balanced’ and ‘nuanced’ by not embedding their articles and stories in any kind of comprehensible or contextual narrative… Likewise, modern ‘consumers’ believe they are being ‘individuals’ and ‘rejecting conformity’ by pursuing their own surface (market-provided) identity, unconnected to the collective weal… Likewise, modern psychotherapists believe they are being ‘rational’ and ‘evidence-based’ by rebranding laziness, conceit, boredom, inattention and so on as isolated, miraculously self-engendering ‘illnesses’, unconnected to consciousness or context (autonomy, family and society)… and so on.

This comes about because the modern mind (adult, civilised, literate) is perpetually focusing. It perceives only isolated things, names and systems in relation to itself. The pre-modern mind (childlike, pre-civ, illiterate) by contrast primarily experiences what occurs as a blended whole. Things, for primal men and women, are not separate from each other or from the witnessing I; they and I are perceived as a unified living gestalt. There is still the power to isolate — to pick things from the whole, to name or symbolise them and relate them together into systems — but this power is a tool which I use.

For the modern mind the tool is using me. It has usurped my conscious experience and is calling itself ‘I’. The modern mind, consequently, can do nothing but focus, name and think. It creates and lives in a universe of (1) separate objects (2) symbolic representations of those objects (3) mind-made systems of those symbols — all of which it takes to be the truth. And because this fragmented and abstract world is part of ‘me’, the modern mind defends it, and the hell which it creates, unto death. If something or someone whole, embedded, contextual, intellectually mysterious, autonomous, simple, intrinsically, unconditionally okay or communicating on a qualitative plane comes along — something that the modern mind can’t quite grasp, can’t quite control — it panics; hard-disk whirrs, error! error! Attack mode engaged:

- Ignore, dismiss, rationalise away…

- Ridicule, laugh at, damn with feint praise…

- Agree, like, buy, attempt to assimilate…

- Annihilate utterly.

This does not apply just to external threats to the modern mind, but to the overwhelming threat of its own [pre-focused] experience — which, because I AM IT, is everywhere, at all times (even into dreams it follows, where it appears as an unfathomable, ineluctable horror).

And so the modern mind is in permanent attack mode. Externally it is constantly on the defense-attack; prowling for threat and looking for means to augment itself. Internally it is constantly ridiculing the voice of its own conscience, constantly suppressing upswells of honesty and constantly fleeing from anxieties it cannot comprehend. The modern mind is constantly working to create boschian hell from it’s own heavenly consciousness, by constantly focusing on isolated bits of its own experience and by blocking out everything else (technical term: ‘noise’).

This modus operandi we register as fixed, staring, creepy, tense, up-tight and stiff.

In a word; successful.